Spirits

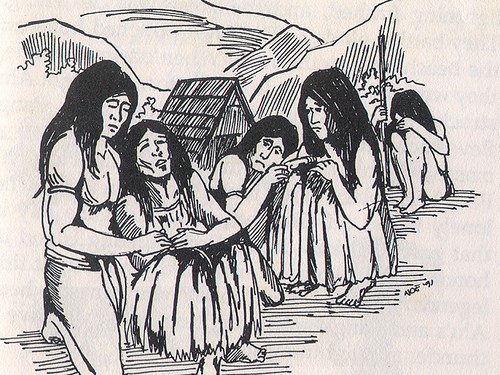

Aniti is the ancient Chamorro word which meant spirit. In its contemporary use, it has evolved to mean evil spirit or demon though some people are using it again to mean spirit.

In various historical documents the term aniti is used to describe the spirit of the deceased person, while in other documents it is used to reference maleficent (harmful) effects on a person. However, the collective use of the word addresses the worldview of the ancient Chamorro. In this cosmological view, the aniti is a force which also finds its way into the everyday lives of the ancient Chamorro. In some instances, the taotaomo’na (people of before) are also considered to be evil spirits who taunt and harm innocent people or those who show disrespect in one manner or another. Hence the term encapsulates both types of spirits and both having influence over the lives of both the ancient and modern day Chamorros.

In ancient Chamorro society, the term aniti referred to soul or spirit. The all-encompassing Christian evangelization efforts by Spanish missionaries that began in the late seventeenth century polarized the meaning of aniti, to refer to something evil.

Aniti changed to mananiti, or the devil. This was a result of a quick introduction of a new religious system known as Catholicism.

Today, aniti is notorious for bad luck or misfortune befalling someone who is deemed as disrespecting the ancestors. Interestingly, the term aniti and taotaomo’na are synonymous to each other yet it is treated differently by way of worldview.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G., trans. History of the Marianas, Caroline, and Palau Islands by Luis de Ibañez y Garcia, 1887. Mangilao, GU.: University of Guam Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, 1992.

Le Gobien, Charles. Histoire des isles Marianes, nouvellement converties à la religion chrestienne… (History of the Mariana Islands, newly converted to the Christian Religion…). Paris, 1700.

Rodriguez, Fred T. “The Humble Man of God: One Man’s Communion with God and Creation” M.Nginge' - Sign of RespectA. thesis, Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, 2004.

Honoring elders

Nginge’ is a term that describes the smelling or sniffing of the back part of an elder’s slightly raised right hand. Elders, or manåmko, collectively understood to have wisdom, are called mañaina. The Chamorro practice of smelling or sniffing was a way of taking in the essence of one’s spirit and pre-dates colonization.

A kind of ritual among Chamorro people, this “smelling of the hand” is still often done upon meeting, as recognition of the importance of showing respect and honor toward elders.

In a slightly bowed position, the giver of this gesture utters either ‘ñora,’ derived from the Spanish ‘señora’ or ‘ñot,’ derived from the Spanish ‘señor,’ for female and male elders, respectively. When this is done, the receiver responds by saying, ‘Dioste ayudi’or ‘God help you.’

In recent times this custom of showing respect has evolved to include sniffing or kissing the cheek of an elder with the same greeting and response.

This custom symbolizes a living cultural institution of respect in Chamorro society.

To find out more about the history of this custom read Pale Eric Forbes’s blog post Man Nginge‘.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Perez-Iyechad, Lilli. “Death: The Expression of Grief.” In An Historical Perspective of Helping Practices Associated with Birth, Marriage and Death Among Chamorros in Guam. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

Topping, Donald M., Pedro M. Ogo, Bernadita C. Dungca. Chamorro-English DictionaryHonolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1975.

Social reciprocity

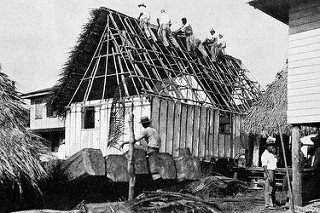

Chenchule’ refers to the intricate system of social reciprocity at the heart of ancient and contemporary Chamorro society. Chenchule’ is a support system of exchange in which families express their care and concern for each other, as well as a sense of obligation to each other while working together to help each family meet its needs. It signifies the core Chamorro value of mutuality expressed in innumerable ways and is meant to sustain the integrity of the Chamorro family and community.

Chenchule’ is further rooted in the core value of inafa’maolek that promotes interdependence within the community so as to provide for the well-being of the whole, rather than that of the individual.

In the past chenchule’ referred to the act of giving, but has come to refer to the contribution itself as well. Chamorros on Guam have begun to use the term chenchule’to describe many types of reciprocation. Up until recent times, Chamorros were more likely to use specific terms to distinguish the various types of assistance exchanged.

These terms helped to identify the type of event it was for, described that it was a form of labor, indicated that it was tangible (touchable), or provided other details. For example, the offering at a baptism reception or child’s birthday might have been labeled regalu, while assistance at funerals given by close friends of the same generation would have been more commonly called ika.

Help and support system

The central theme of chenchule’ has remained strong through the years. Chamorros feel compelled to help and support one another through times of both celebration and grieving. Chamorros also gain a sense of social esteem through fulfilling such obligations or through being able to publicly demonstrate the amount of assistance available to them. Part of one’s Chamorro identity rests on the particular system of reciprocal obligation of which one’s family is a part.

In ancient times, certain reciprocation would have taken the form of ålas, or traditional turtle shell valuables, given in exchange for some special service performed or favor bestowed. As Chamorro society transformed into a money-based economy, this living practice of reciprocity transformed as well.

Chenchule’ today is demonstrated most obviously at celebrations of life milestones—taking the form of different types of labor, food, drink or other supply contributions, gifts, or money at occasions such as weddings, childbirth, and funerals. At such events, a chenchule’ box usually graces the gift table, decorated in a specific design (such as a treasure chest, water well, or theme character) or is otherwise made attractive. Guests insert envelopes of money, labeled with their family names and oftentimes village of residence, through a slot on the box’s top. At weddings, chenchule’ can also be found on the dance floor during a money dance in which guests line up to dance with the bride or groom and pin paper money onto the newlywed’s garments during their turn.

Over the years, Chamorro life-cycle events have become celebrated more often and have become more elaborate. Money has become a favored form of chenchule’, however, the contribution of labor, food, drink, and other supplies for a celebration remain a widely practiced form of chenchule’. Chenchule’ is now often documented in writing among families, recording the date of the contribution and its type and amount. This partially developed as a way to track contributions so that the receiving party would equitably reciprocate the giving party during a future time of need.

Further, this tracking system was developed to recognize all those who have given from the heart – the most valuable aspect of chenchule’. Chenchule’ debts—both those owed and to be paid, are inherited by the next generation. The ongoing nature of chenchule’ between generations within a family works to strengthen and sustain ties of mutual obligation and support between Chamorro families.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Department of Chamorro Affairs Research, Publication, and Training Division. Chamorro Heritage: A Sense of Place; Guidelines, Procedures and Recommendations For Authenticating Chamorro Heritage. Hagåtña: Department of Chamorro Affairs Research, Publication, and Training Division, 2003.

Iyechad, Lillian Perez. An Historical Perspective of Helping Practices Associated with Birth, Marriage, and Death Among Chamorros in Guam. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

Pacific Worlds: Guam. “Chenchule’”. (Accessed 18 June 2012)

Political Status Education Coordinating Commission. Hale’-ta – I Ma Gubetnå-ña Guam: Governing Guam Before and After the Wars. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1994.